StorySpotting is a weekly or kinda-weekly series about folktales, tropes, references, and story motifs that pop up in popular media, from TV shows to video games. Topics are random, depending on what I have watched/played/read recently. Also, THERE WILL BE SPOILERS. Be warned!

I watched Encanto in the movie theater and then went and immediately watched it again. It is a stunning, deeply moving film. It also emotionally knocked me on my ass for a whole day.

Where was the story spotted?

Encanto (Disney, 2021.)

What happens?

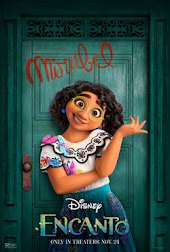

The main characters of the movie, the members of the Madrigal family, all have special supernatural powers (except for Mirabel, our hero). They gain their powers from a magic candle, gifted once upon a time to the family's matriarch.

What's the story?

All the powers granted to the Madrigal family have their counterparts in folklore and legend. Since this is one of my areas of interest (or nerdiness) as a storyteller, I couldn't pass up blogging about them. Let's see in order:

Pepa Madrigal - Weather control

In a

folktale from Cape Verde two girls encounter three fairies, with vastly different results. Similarly to the Frau Holle story the hard-working girl is rewarded, while the lazy girl is punished. Both reward and punishment, however, are unusual. Good Maria gains powers so that "when she laughs the rain may fall, and when she smiles the weather thickens", while Bad Maria gets powers so "when she smiles, a strong wind blows, and when she laughs, a tempest uproots all the trees on the shore and wrecks all the ships at sea." Their mood, just like Pepa's, directly affects the weather.

Julieta Madrigal - Healing

Julieta, Mirabel's mother, has the magic power to heal people with the food she cooks. It is one of the loveliest symbolic powers in the movie. She is one in a long line of legendary women, both of folklore and history, who knew the secrets of folk remedies and healing herbs. In European folklore, we have famous ladies such as

Biddy Early or

Anne Jeffries, or Hungary's lesser known but endlessly fascinating

Macska Róza (Rose of the Cats). There is a lovely

folktale from Tajikistan about a brave girl who sets out to find a magic plant, and learns the art of healing in the process. From the Maya South America,

there is a story about a wise old woman who cures toothaches and thus saves her village.

Bruno Madrigal - Visions of the future

Seeing the future is not exactly rare in folklore and mythology. Practically everyone is doing it, from queens to strange old beggars on the roadside. But Bruno's story has two components: the fact that he sees the future,

and the fact that his family basically exiles him for it. And that, in itself, is also a folktale type. It's numbered

ATU 725 ("The Dream"). In it, a boy usually sees a dream or a vision of how in the future he will be a great sovereign, and his father/parents will bow down to him (Joseph, anyone?). In anger, the family kicks him out, and he has to go through a whole lot of ordeals until the vision inevitably becomes reality. (The Motif Number for this is L425). Interestingly, this tale type also exists with a female hero in a

Greek collection.

Dolores Madrigal - Sharp hearing

Dolores can hear a pin drop from a mile away. Unusually sharp hearing, actually, is not at all unusual in folktales. It even has it's own motif number:

F641, Person of Remarkable Hearing. These heroes usually appear in the folktale type ATU 513,

Extraordinary Companions, and they are a staple member of the team in almost every variant of the story. They can hear the grass grow, ants walk, or a feather fall halfway across the world. They usually aid the tale's main hero by telling him of impending danger.

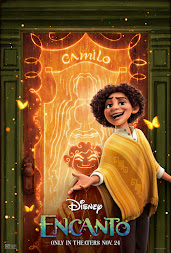

Camilo Madrigal - Shapeshifting

Continuing with the cousins: Camilo can take on the appearance of other people, and change his body at will. Now, while shapeshifting is quite common in folklore, taking on other humans' appearances is more of a rarity. In general, human shapeshifting is reserved to... people who are not quite human. In a

Roman myth, for example, Vertumnus, minor god of the changing seasons turns into various attractive men to seduce a reclusive nymph. In

another myth (also from Ovid's aptly named

Metamorphoses) a girl named Mestra gains the power to change her shape at will, and she uses it to get away from her abusive father. In the

medieval ballads about Robin Goodfellow (a.k.a. Shakespeare's Puck) he is half mortal, half fae, and can change his shape into whatever he wants to be, including humans and animals. Since Camilo has a trickster nature in the movie, Robin is probably closest to him in personality. Another shapeshifting trickster spirit that appears as various humans is

Rübezahl, the goblin king of the Silesian mountains.

Antonio Madrigal - Animal speech

Antonio, the youngest of the Madrigal children, has the power to talk to animals. Once again, this is a classic. The motif number is

B216 (Knowledge of animal languages) or B217 (

Animal language learned). There are too many tales to list, although unfortunately many of them involve wife-beating or even murder. So I'm only highlighting some that are better. The

legend of the Da-Trang crabs from Vietnam tells of a man who gains a magic pearl that helps him understand the language of all animals. He uses his powers for good in various creative ways (until one day he loses the pearl, and his senses with it). The

Italian tale where a clever boy named Bobo learns animal speech ends better: he uses his gifts to help people, and is eventually elected Pope with the help of a pair of doves. A

boy named Jack from the Traveller tradition also puts his knowledge to good use, and grows rich from the secret he learns from the birds (about how to find hidden treasure while the trees go dancing). Finally, a personal favorite: in a

Japanese tale an old man receives a listening hood that allows him to hear the speech of animals and plants. He uses this knowledge to help them, and also the people who don't realize the damage they are doing to nature.

Luisa Madrigal - Super strength

Super strength in folklore is as common as dirt, but it becomes a tad more interesting when we talk about super strong women. Many people might be familiar with the picture book

Three Strong Women, which is based on a Japanese folktale. In it, a three-generation family of brawny ladies teach an important lesson to a sumo wrestler. It took me a while to track down the original story, about a strong girl named Oiko, in

this folktale collection. She also trains a sumo wrestler to be stronger, and also teaches a lesson to villagers who try to mess with her.

Isabela Madrigal - Flower power

Isabela makes flowers grow everywhere (as well as "a hurricane of jacarandas, strangling figs, hanging wines", which is a line from her song I adore). She reminded me of a princess from Hungarian folklore:

The Princess Who Makes the Forests Green and the Meadows Bloom. Wherever she walks, she brings nature to life. An Indian princess has similar abilities in a tale titled

A story in search of an audience - here, she receives her gift because her pregnant mother listens to a legend no one else is willing to hear. In another, even more beautiful tale from India, a girl has the power to turn herself into a

Flowering tree, providing fresh flowers for her family to sell. In the same collection we can also read about

The Princess of Seven Jasmines, from whose lips jasmine flowers drop when she laughs. By the way, flowers blooming from a girl's laughter, footprints, or hair is a common motif in folklore (numbered H71.4 or D1454.2.1 in the Motif Index). It is usually a blessing that distinguishes her as a "good bride" or a "kind sister."

Mirabel Madrigal

Isn't it the entire point of the movie that Mirabel doesn't have a superpower? Well, yeah, it is. But her story is not without parallels anyway. There is a dark prophecy about her, one that everyone thinks means she will wreck the family. This reminded me of an Icelandic folktale, titled

Hild, the Good Stepmother. While it is about the No. 1 rule of folklore that a prophecy always come to pass, this story goes in the opposite direction. A princess is foretold to bring ruin to her family before she turns 18: burn down the palace, get pregnant out of wedlock, and kill a man. Her stepmother, however, helps her figure out ways to bypass all three on technicalities, and in the end, she lives happily ever after with her family. (Find another version

here.)

Encanto

And since the house and the home of the Madrigal itself is a character in the story, I can't miss mentioning the

Encante of Amazonian

legends: a hidden, magical city full of magical creatures. It is usually believed to be the home of the

encantados, shapeshifter people that like to appear as Amazon river dolphins. People who are lucky enough to make the journey to the Encante usually return wiser, and kinder, than before.

Conclusion

I have a soft spot for superpowers in folklore (I even wrote a

book about it). And

Encanto does an excellent job of using them.